Wikipedia (CC)

The Śaiva Age was from the fifth to the thirteenth centuries CE, when a series of modes of worship proliferated and were adopted by many rulers as sanctioned practices even while many were appropriated by the Brahmanical order. Shaivisim has nevertheless remained a heterodox custom, with diverse minority traditions.

Shiva with Trisula, worshipped in Central Asia. Penjikent, Uzbekistan, 7th–8th century CE. Hermitage Museum (Wikipedia CC).

These other forms of worship included not only Buddhism and Jainism but also devotion to Śiva, Vishnu, Surya, and the goddess Shakti in various forms; worship of Śiva was the most common among these heterodox practices. By the eleventh century, also joining the mix was Sufism, characterized by community forms of worship with song and poetry known collectively as bhakti.

(CC)

If Buddhism, Jainism, and Ājivikism were largely Magadhan traditions, Śaivism’s origins are a mystery. The Lord Śiva might have been a later reconstruction of various local deities that were united with the divine Rudra of Vedic lore.

Wikipedia (CC)

One possibility is that it emerged in Harappa in an early form, as the austere god that all Harappans emulated in their commitment to a type of physical asceticism. Indeed, it may have been that very self-discipline that helped create an ordered urban life that was able to build up a substantial material and symbolic surplus from trade. But it is also conceivable that Śaivism’s earliest practices were found in southern India and amalgamated with phallic worship in various other parts of the subcontinent.

AP (CC)

There were numerous Śaiva sects, with each one typically derived from an ascetic guru who had the divine power of mantra to make a ritual connection between his followers and either Śiva or his consort Śakti. These sects were formed on the basis of learning mantra at the feet of the guru, through various grades of initiation and access to texts called Tantra. But Brahmin devotees also worshipped Śiva; they traced this tradition to the form of Rudra-Śiva, which appeared in the Shvetashvatara Upaniśad, a fifth-century BCE text associated with the Yajurveda.

Wikipedia (CC)

Whereas Brahmin Śaivites followed the practices of varnāśramadharma through their formation and validation in Puranic literature, their non-Puranic counterparts had a longer and perhaps more colorful existence. In the Pashupata sect, strange behaviors were expected from initiates who passed through the first stage of initiation: “These include pretending to be asleep in public places, making his limbs tremble as though he were para- lyzed, limping, acting as if mad, and making lewd gestures to young women.” (Gavin Flood, 2003).

sivasakti.com (CC)

Although it is useful to see how Śaivism can be interpreted as both an insider and outsider practice in relation to Brahmanism, there is little doubt that its established form in Brahmin sects can only be traced to the Gupta period (third to sixth century CE) with the development of the Puranas, a set of sectarian texts on the mythical reconstruction of particular cosmogenetically derived traditions of worship. The Śiva Purana not only tells stories about Śiva but also instructs devotees on where they should worship.

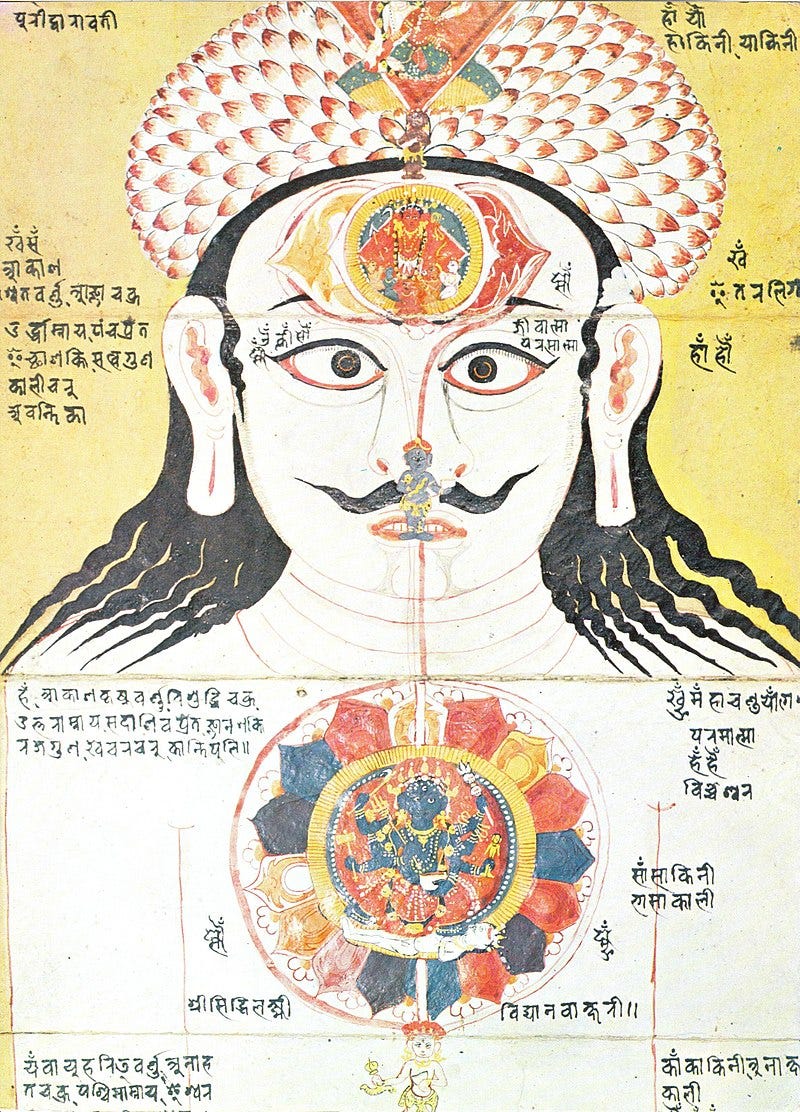

Tantric art. Clockwise from upper left: Vajrayogini (Buddhist), Sri Yantra (Hindu), Chakra illustration, Kalachakra Mandala, Dakini Wikipedia (CC)

Tantra appeared in the early centuries of the Common Era in both Buddhist and Śaivite practices. Tantra, which comes from the word “loom,” was built around secret societies that created stages of initiation involving heterodox practices, as in the Pashupata example given earlier. Over time, a separate Tantric identity was created within Buddhist and Śaivite communities; its adherents lived in exclusive communities, mirroring the secret and codified ritual lives of dvija men but having entirely different practices.

Svoboda (1986) CC

Some practitioners (tantrikas) were ritually obliged to partake in the Five Forbidden Things: alcohol, fish, meat, parched grain, and sexual intercourse. By violating ordinary social norms, Tantric sects created alternative rules to follow but also demanded the cultivation of the yogi (one who has mastered discipline—yoking) by using bodily practices to unify the subtle elements of the self with Śiva and Śakti.

British Museum (CC)

When kings adopted Tantric Śaivism or Buddhism, it is helpful to ask what modes of accommodation were in fact sought or made. The religious studies scholar Alexis Sanderson points out that the early royal patronage of Śaivism had several motivations, but it was facilitated by the way Śaivism refashioned itself to constitute a “body of rituals and theory that legitimated, empowered, or promoted key elements of the social, political and economic process that characterize[d] the early medieval period.” (Sanderson, 2009).

Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, ed. Shingo Einoo (Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Cul- ture, 2009), 41–349.